"I like dresses to be sober, and accessories to be wild...."

For years now, I've worn 3D-printed jewelry, to the exclusion of all other materials. The pieces' lack of content is what I find appealing: just as the medium is the message, shape is the material. There is a motion, a liveness. Rather than whisper I am expensive, a 3D-printed piece asserts: I am. It does something, rather than seeking to register as something. It’s the appeal adorning oneself in verbs, not nouns.

Meanwhile, just a stone’s throw away from AFFALÉ H.Q., in New York City, is P.E. Guerin, an institution that I have never entered, for fear that I would never want to leave:

“P.E. Guerin is the oldest decorative hardware firm in the United States, and the only metal foundry in New York City. The company was started in 1857 by French immigrant Pierre Emmanuel Guerin and has been at its current location on Jane Street in Greenwich Village since 1892. One of the pioneers in artistic metalwork in New York City, examples of his production can still be found in various public buildings, parks and important residences throughout the city and the country.”

You could say, I prefer verbs to adorn humans, and nouns to adorn homes. But when it comes to clothes? Naturally, something exactly halfway between the two. The vision I have for AFFALÉ trim is to imbue that precise, idiosyncratic midpoint with every last shank button and frog closure.

In terms of garment-affective power, trim has this sort of grounding, embodied quality that’s impossible to replicate with thread and dye alone. But few designers, perhaps only higher-ups at the larger houses, are able to directly manipulate this quality. The legacy bulk-sourcing model, where creativity is directly proportional to cost, works against them.

As a result, not only do many garments prominently feature elements on which the designer had no input, the true magnitude of the vision they had for that garment is never realized. Fashion is nothing if not the bending of physical reality towards more tasteful ends. But limitless creation with trim is another matter altogether—even more so for an upstart brand like AFFALÉ.

Much technical wonder is to be wrought, as I dive deep into 3D printing and generative design, and as always, you’ll get read about every last pioneering bit of it. First, however, a bit more in the way of backstory. Limitless trim is one of the most revolutionary aspects of what I’m doing with AFFALÉ, and I should first explain why I see limitless trim as so vital to my creative vision.

Little Blue Book

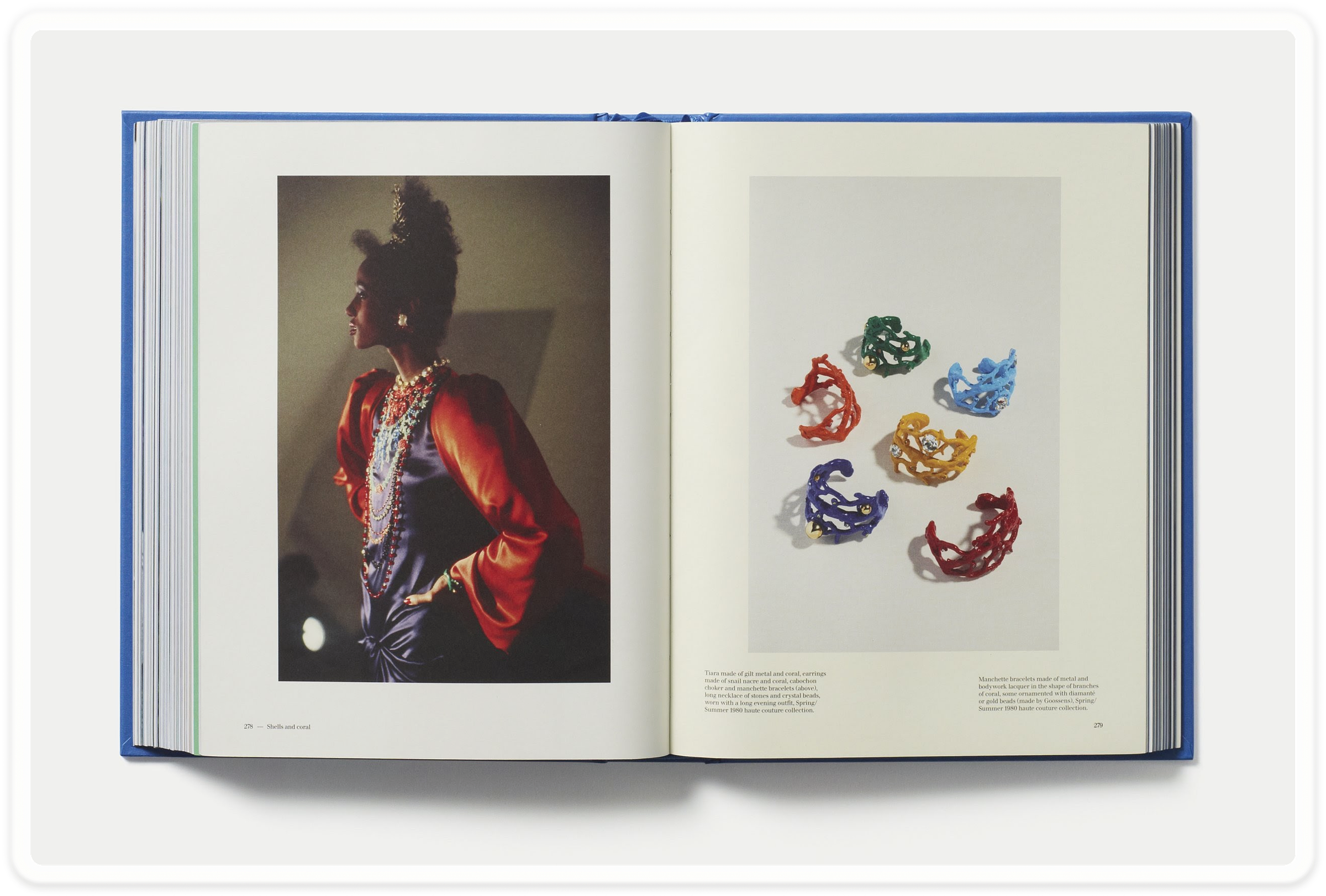

“One can never overstate the importance of accessories. They are what turns a dress into something else. I like dresses to be sober, and accessories to be wild.”

⏤ Yves Saint Laurent, 1977

When I first moved to New York City, I purchased Phaidon’s entire fashion collection for my living room, because dammed if I was going to turn into one of those girls with that Tom Ford book sitting on my coffee table, just because my big city dreams finally came true.

One of the included volumes was a stout, very blue little book titled Yves Saint Laurent Accessories. Total fashion neophyte I was at the time, I assumed the book was blue for Yves Klein, despite knowing Saint Laurent was in fact a separate Yves. I dunno. Maybe they did a collab at some point. Yves x Yves. Yves².

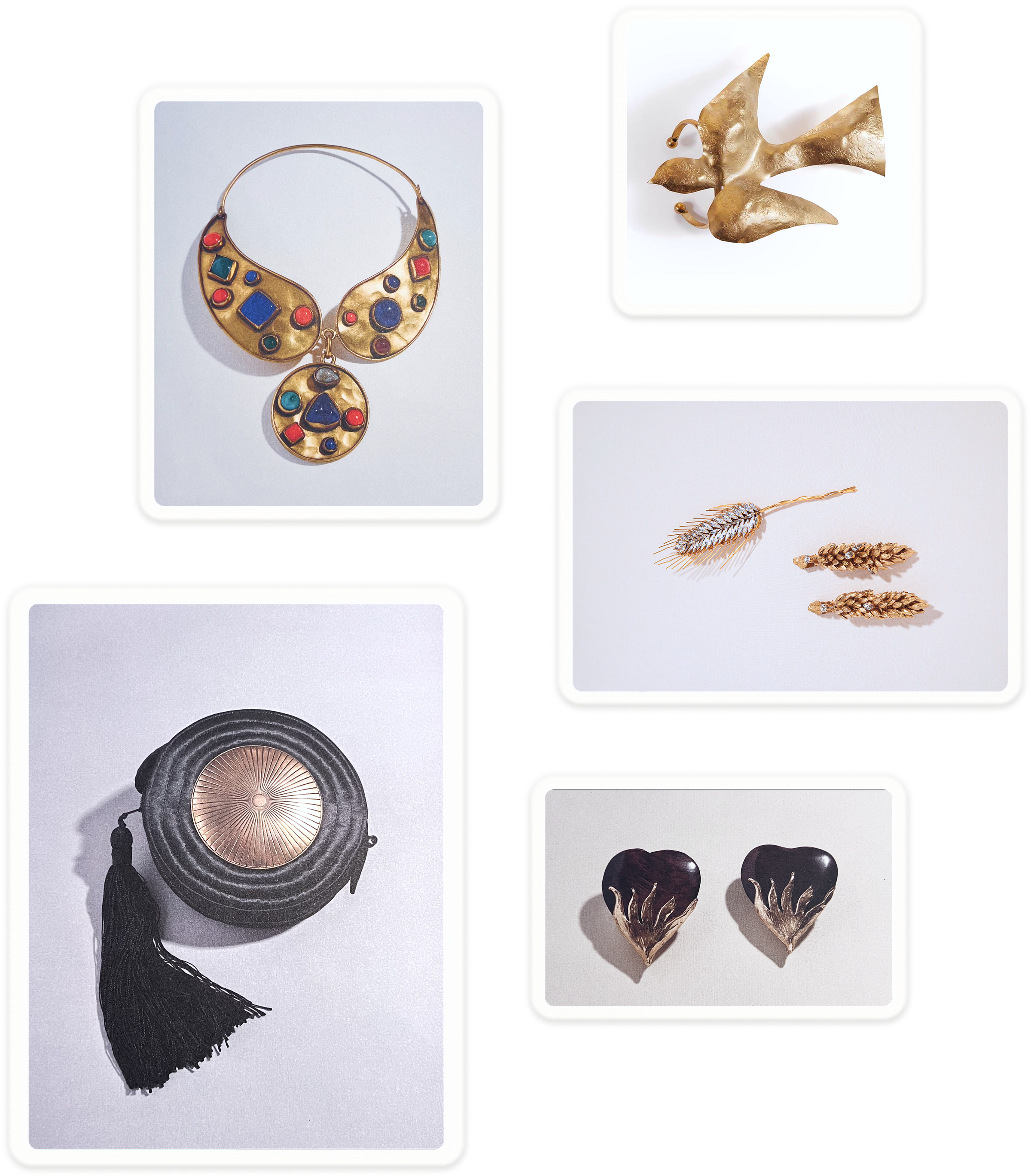

But, Yvesapaloozas aside, I was instantly taken by the book’s contents. I’d yet to see accessories so singular and exquisite, and still today haven’t found a similar body of work that surpasses Saint Laurent’s in sheer breadth of imagination.

Somehow, the pieces all hang together, without ever relying on any superficial gimmicks or distinct flavor of baroqueness. This is very difficult to achieve as an individual designer, let alone as the head of a major house in collaboration with dozens of craftspeople and artisans.

This isn’t to say Saint Laurent abandoned all visual referent in favor of purely abstract geometries, as many artistic jewelry designers, armed with their parametric design software, are wont to do today. Something that stuck out to me as a designer was how generative just a handful of basic forms like hearts, crosses, doves, feathers were for Saint Laurent. He wasn’t continually pulling new ideas out of thin air—rather, he was always growing and evolving elements of his artistic core.

“There is another aspect that sets a couturier apart from a designer, and that is that he or she works in an imaginative universe of his or her own, using and returning obsessively to a handful of different themes and images, which are repeated and reworked until they form a veritable personal mythology.”

“Veritable personal mythology” is a heady euphemism for “style," but in Saint Laurent’s case, it’s only barley adequate. Watching the motif of, say, the dove evolve over several decades across dozens of collections, from small buttons and earrings, into statement bracelets and finally into the showstopper that is whatever one might call that funky, shoulder-mounted, dive-bombing dove-thing, one notices Saint Laurent isn’t using accessories to tie just the looks and collectionstogether—he’s threading these highly personal meanings through every design he creates, continually binding the house’s entire creative output into a unified whole.

But against this backdrop of motivic development, emerges a more subtle aspect of Saint Laurent’s perspective: accessories exist on a continuum.

A button is a brooch that just happens to pull double-duty as a fastener. A handbag is just an earring scaled up so you can carry it in your hand. Mount two belt buckles on a frame, and you have yourself a pair of eyeglasses. The forms could be so fluid, because an accessory was never imagined to be an end in itself. Instead, the accessories and the garment constituted a unified whole that emerged out of the interplay of the two: sober dresses, wild accessories.

“For Saint Laurent, accessories had a value far removed from their accepted one and connotations quite different from those we normally associate with them. For him, these little nothings' (a phrase that, of course, etymologically presupposes 'some-thing) - pieces of jewelry, belts, shoes, hats - played a vital part. They punctuated an outfit or ensemble in all senses of the word, articulating, accentuating and fixing it, as a pastel artist fixes his work. As Saint Laurent put it, ‘The accessory is the part, to my mind, that pulls the whole look together and gives it a unique quality.’”

As a designer, reframing accessories as a continuum was nothing short of mind-bending. The look is the look, the atomic unit of expression. Considered in isolation, a dress remains unfinished, a substrate still to be shaped, lacking punctuation, and possessing the sensation of a run-on sentence the length of a novel. A professional orchestra might perform a score well enough on its own, but, without a conductor responsible for the articulating, accentuating, and fixing, the piece will come off as blurry, lacking a focal point.

And, crucially, in Saint Laurent’s case, accessories were not just a continuum creatively, but also logistically. The luxury of the latter is what enabled the former. Of course, the glamorous budgets and limited scale of designing haute couture didn’t hurt, but Saint Laurent had much more than that going for him—world-class artisans, notably goldsmith extraordinaire Robert Goossens, and one Loulou de la Falaise, Saint Laurent’s right-hand woman, and partner-in-crime on all things accessories:

“[Loulou] was not only an inspiration to Saint Laurent, but also the couturier's partner in thought, able to interpret his ideas. She shared his taste and even, one could say, his wild imagination. Until the house closed in 2002, it was she who briefed the various craftspeople and trade members and ensured that the jewelry, hats, shoes, gloves and scarves they produced accurately matched what Saint Laurent had envisioned and so met with his approval.”

Not all designers are so fortunate. On the ground, in the trenches, accessories can’t possibly be a continuum creatively to most designers because they aren’t a continuum logistically. The hope for one imagination to engage in fluid creation is dashed against the rocks of practicality. Categories like garment trim, jewelry, eyewear, and handbags are largely siloed under the legacy manufacturing practices. Each have their own machines, moulds, tooling; each have their own design software, merchandising strategies, and and e-commerce tabs.

Truly “limitless trim”—what I’m calling the ability to imagine the form of any accessory and bring into being physically, near-instantaneously, and cost-effectively—doesn’t yet exist for designers. It’s a principle-agent problem: the designers who can conjure up entire worlds, in a manner similar to Saint Laurent, have no reference for what’s technically possible, much less the intuition for how to tie it all together into a scalable system. And the technologists who would pioneer such a system lack the creative eye to imagine the applications that would make building such a system worthwhile in the first place.1

Hello, World

‘Most of [Picasso’s] paintings conjure space that is cunningly fitted to the images that inhabit it...[but] when the space becomes real, the dynamic jolts.’

— Peter Schjeldahl, Another Dimension: Reconsidering Picasso the Sculptor

But recent advances in additive manufacturing have me feeling optimistic it can be done, now. The pieces are all there. And with AFFALÉ, I think I’ll manage to pull them all together.

So it was one morning several weeks ago when, upon arriving at the office, I was greeted by a very lovely sight:

And a veritable Tasmanian Tornado of an unboxing later…

…and, finally:

Limitless trim. Much more to come.

plus chic, tu meurs,

—jane

Enter the keyword “jewelry” into the search bar of any major online repository of 3D models, and you’ll find “useful” things, like jewelry boxes and organizers, necklace stands, and ring sizers, outnumber actual pieces of jewelry by a factor of at least three.